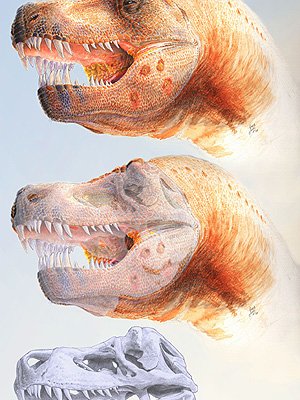

University of Queensland research is opening up a new insight into the lives of the mightiest of all dinosaurs, and it isn’t pretty.

UQ palaeontologist Dr Steve Salisbury, together with American colleagues, has found Tyrannosaurus rex and its close relatives suffered from a deadly infectious disease similar to one that occurs in birds today.

“This is the first time that we have found evidence for an avian infectious disease in dinosaurs,” Dr Salisbury said.

Dr Salisbury said the evidence came from unnatural holes in the back of their lower jaws. The research has been published in scientific journal PLoS ONE.

“Some of the world’s most famous T. rex specimens have these holes in their jaws, including ‘Sue’ at the Field Museum in Chicago,” he said.

Dr Salisbury said tyrannosaurs were known to have marks on their heads from biting each other, presumably during territorial disputes or mating, but the holes he and his colleagues were interested in were at the back of the jaws, too far back to be bite marks.

“These holes don’t show any of the normal characteristics of bite marks,” he said.

“It’s as if someone took to the jaws with a hot poker. Some specimens look like Swiss cheese.”

“We now believe that these holes are caused by an infectious disease called trichomonosis.”

He said trichomonosis was a modern avian disease caused by a parasite and is most prevalent in pigeons, which are generally immune.

“Birds of prey are particularly susceptible to trichomonosis if they eat infected pigeons,” he said.

“Adult birds can then pass the disease to their nestlings through beak-to-beak contact.”

Dr Salisbury and fellow researchers Ewan Wolff, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Jack Horner and David Varricchio, from Montana State University, examined many T. rex fossils as part of their study, including the most famous and complete T.rex of all ‘Sue’.

“It’s ironic to think that an animal as mighty as ‘Sue’ probably died as a result of a parasitic infection. I’ll never look at a feral pigeon the same way again,” he said.

He said the link in disease is not surprising given the evolutionary relationship of dinosaurs to birds, but the discovery of a likely candidate for such a disease link represents a major step forward in our understanding of disease history in birds and their dinosaurian precursors.

“The discovery provides an insight into the dinosaur immune system,” he said.

“The symptoms seen in tyrannosaurs indicate that their immune response to the disease is almost identical to that found in living birds.”

Dr Salisbury said the disease appeared to be quite common in tyrannosaurs and would have been deadly to those that were infected.

“As the parasite takes hold, lesions form around the jaw and inside the throat, eventually eating away the bone,” he said.

“As the lesions grow, the animal has trouble swallowing food and eventually starves to death,” he said.

He said tyrannosaurs are the only dinosaurs that appear to have had this disease, so the one of the challenges the researchers faced was explaining how it was spread.

“We don’t think it is a coincidence that a significant number of adult tyrannosaur specimens show both face-biting marks and evidence of a trichomonosis-like disease,” Dr Salisbury said.

“Fighting and specifically head-biting would have been an ideal mechanism for spreading the disease among tyrannosaurs.

“We can see similarities with what has been happening to Tasmanian devils recently, where a malignant and debilitating oral cancer is being spread by animals fighting and biting each other’s faces.”

Media: Dr Steve Salisbury (+61 7 3365 8548 or +61 407 788 660) or Andrew Dunne at UQ Communications (+61 7 3365 2802 or +61 433 364 181).

Images: Karen Poole at The University of Queensland (+61 7 3365 2753, k.poole@uq.edu.au); for images of ‘Sue’ contact Jarice Barrios at The Field Museum (+1 312-665-7794, photos@fieldmuseum.org).

.jpg)