New research reveals conservation initiatives often spread like disease, a fact which can help scientists and policymakers design programs more likely to be taken up.

The study, including University of Queensland researchers, modelled how conservation initiatives are adopted until they reach “scale” – a level where they can have real impact on conserving or improving biodiversity.

UQ’s Professor Hugh Possingham said understanding the underlying factors that lead to initiatives reaching scale was critical to savings species and ecosystems globally.

“By understanding what makes conservation efforts contagious, we can redesign future initiatives to boost their uptake,” he said.

“The research suggests that one key factor is to facilitate contact between those who’ve already taken up a new initiative and those who might potentially adopt it.

“For example, one community that has established local marine protections talks about what they’ve done and what the benefits are to another community considering doing something similar.”

The research leader, Imperial College London’s Dr Morena Mills, said conservation initiatives – like managing fishing resources and offsetting land for nature – were critical for protecting biodiversity and the ecosystems that help provide us with clean water and air.

“We found that most of these initiatives spread like a disease, where they depend on a potential adopter catching the conservation ‘bug’ from an existing one,” she said.

“We hope our insights into how biodiversity conservation initiatives spread will allow practitioners to design them so that they reach scale, which is critical for enabling them to make a tangible, lasting impact.”

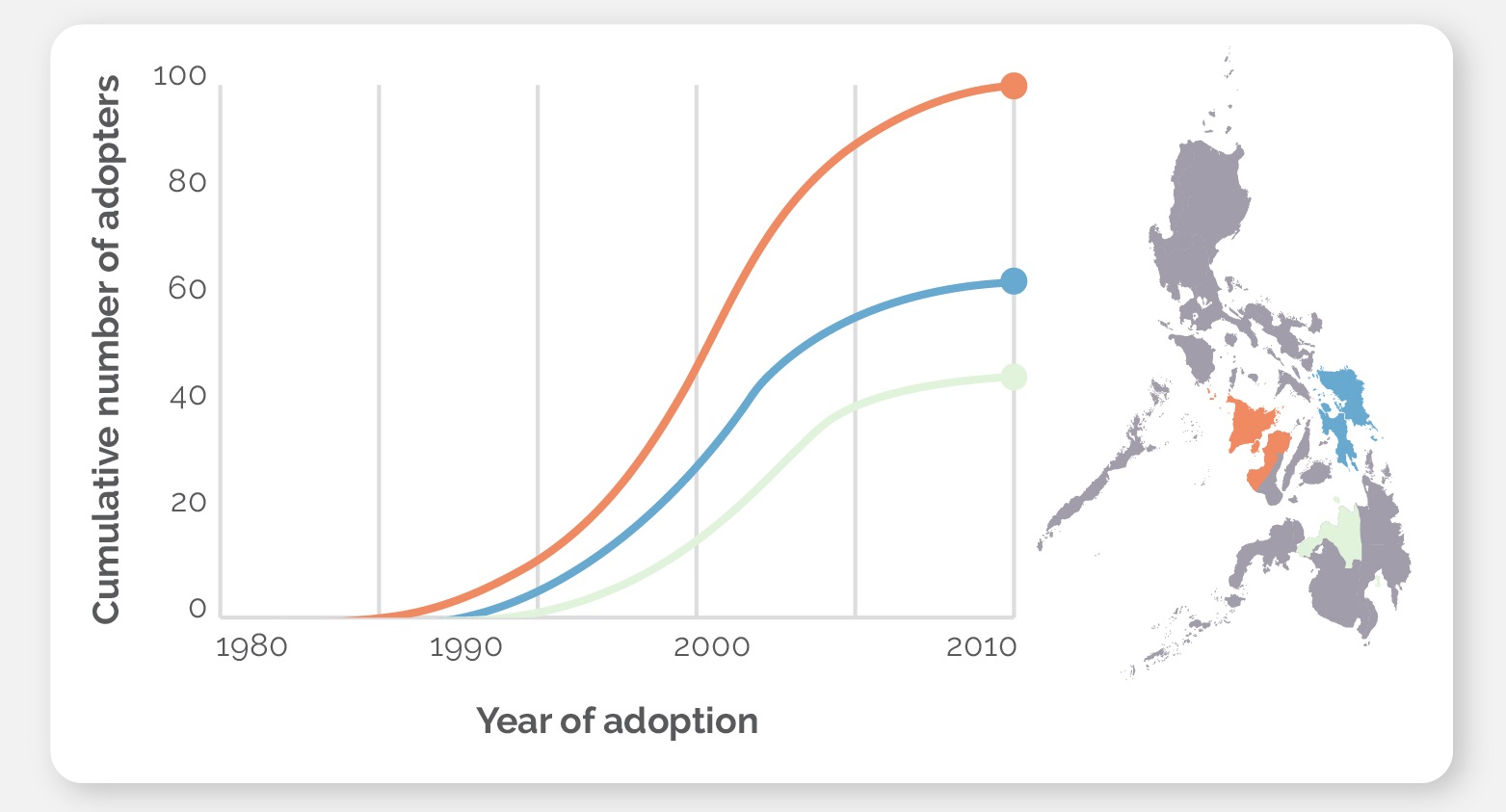

The research looked at 22 conservation initiatives of varying scales across the globe to see how they spread, and how fast.

The research looked at 22 conservation initiatives of varying scales across the globe to see how they spread, and how fast.

“The initiatives ranged from villages introducing protections around local marine sites to governments designating areas as international World Heritage sites, including state and privately protected areas,” Professor Possingham said.

“We found that 83 per cent of the schemes followed a slow-fast-slow model, where initial adoption is slow as few people take it up, but then grows quickly as more early adopters connect with potential adopters.

“Finally, the rate slows again as all potential adopters have either taken up the scheme or refused it.”

The team said further insights were needed, as no initiative in the study had the desired properties of being taken up quickly, and being taken up by the majority of potential adopters.

Most initiatives had one of these properties, with more than half being adopted by fewer than 30 percent of potential adopters.

“We are seeking to understand more about how local context facilitates or hinders spread, to help more initiatives reach scale,” Dr Mills said.

The research has been published in Nature Sustainability (DOI: 10.1038/s41893-019-0384-1).

Image above left: while the mechanism of initiative spread is mostly similar, the uptake rate and extent of adoption is context specific.

Media: Professor Hugh Possingham, hugh.possingham@tnc.org, +61 434 079 061; Dr Matthew Holden, m.holden1@uq.edu.au, +61 406 557 706; Dominic Jarvis, dominic.jarvis@uq.edu.au, +61 413 334 924.

.jpg)