University of Queensland research reveals that spring, rather than summer, is the peak time for tick paralysis in dogs and cats and there are cases year-round.

A team led by Professor Stephen Barker at UQ’s School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences analysed 22,840 cases across 20 years of veterinary records in four regions along Australia’s east coast.

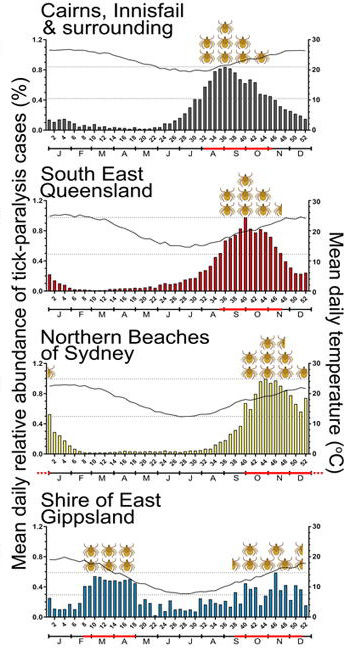

“We found that there were tick cases in pets at veterinary hospitals all year in all of the regions we studied, even in the coldest winter months,” Professor Barker said.

“It’s definitely a wake-up call for pet owners to protect and check their pets all year round.

“The records also showed the biggest danger period for dogs and cats occurs in spring and not in summer as most people would expect.

“Around Cairns and Innisfail in far north Queensland the peak of cases at vet surgeries was in August and September, in southeast Queensland it was September and October while in Sydney’s northern beaches it was October and November.

“This appears to be when the eggs laid by female ticks the previous summer hatch to pose the biggest threat.

“The number of cases actually drops off through the hottest summer months of January and February in all regions.”

The research also revealed that the Gippsland region in western Victoria had two tick seasons each year – from February to April and then again from mid-September through October.

The research also revealed that the Gippsland region in western Victoria had two tick seasons each year – from February to April and then again from mid-September through October.

Professor Barker said the number of pets being taken to a vet with tick paralysis indicated the tick infestation intensity in any given year.

“We lined up the vet data to weather records and saw that variations in temperature and moisture in summer determines how bad the tick season is the following spring and summer,” he said.

“Ticks are quite sensitive to the weather, which explains why some years are much worse than others.

“If the weather is quite dry and hot in January and February, many eggs will die but a mild and wet summer means a high hatching rate and a bad tick season in the following spring.”

The team has developed a computer model to make predictions for future tick seasons, allowing for warnings to pet owners and to help vets be prepared.

“Treatment for tick paralysis is costly and not always successful depending on how long the tick has been on the animal,” Professor Barker said.

“The better warned and prepared we can be, the better the chance of protecting our pets.”

The study is published in International Journal for Parasitology.

Media: Professor Stephen Barker, s.barker@uq.edu.au; +61 448 628 094; UQ Communications, communications@uq.edu.au, +61 429 056 139.

.jpg)