How can two people come up with two completely different Lego models while working from the same instructions?

A University of Queensland School of Psychology study has found it can depend on who people believe wrote the instructions.

Researcher Dr Katharine Greenaway said receiving instructions from someone considered ‘similar’ was more effective than following orders from someone ‘different’, even if the content and method of delivery were identical.

“We explored whether sharing an identity with someone changes the way we communicate with them,” she said.

“This research shows that breakdowns in communication can happen because of identity-related differences.

“For example, the disintegration of the $125 million Mars Climate Orbiter and the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger are commonly cited as being caused by communication failure between two different groups of engineers, so there are wider implications.”

Building on past studies that showed people can struggle to communicate with others of different cultures, gender, age, work groups and sexual orientation, the UQ team gave two groups an unopened box of Lego.

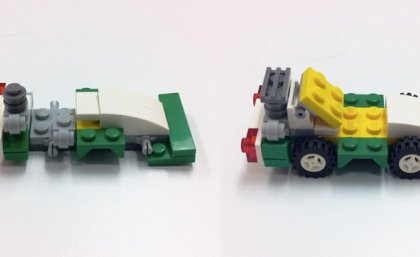

Tasked with completing 17 steps in 20 minutes, one group was told the instructions were created by a fellow group member, while the other group was told they were formulated by a member of the opposite group.

The groups were then scored on the number of steps successfully followed, the number of bricks left over and their response to a series of questions measuring motivation, confidence and impressions of the quality of instructions.

“In one study, participants completed Lego models with three more correct pieces on average when they received instructions from someone in their own group compared to another group,” Dr Greenaway said.

“Not only did participants perceive the instructions to be better if they believed they came from inside the group, they also produced better models as a result.

“The perception that we have understood someone and they have understood us – that we’ve connected, basically – is the basis of successful communication.

“Shared identity can facilitate that feeling of connection, because we believe the other person ‘gets us’ and that improves our ability to communicate.”

The findings of the research are published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, a leading industry publication.

Dr Greenaway collaborated on the study with Professor Alex Haslam from UQ and Dr Ruth Wright, Professor Katherine Reynolds and Ms Joanne Willingham from the Australian National University.

Media: Dr Katharine Greenaway +617 3346 9563, k.greenaway@uq.edu.au; Robert Burgin at UQ Communications, +617 3346 3035, 0448 410 364 or r.burgin@uq.edu.au.

.jpg)