An international research team including experts from The University of Queensland has looked to cleaner fish to appreciate how humans may have evolved to punish free-loaders.

Published today in leading journal Science, the research shows that understanding the behaviour of self-interested cleaner fish in response to personal loss may be a key step toward understanding why humans find it necessary to punish a third party when they receive no direct benefit.

Small fish known as cleaners are found on coral reefs in the Indian and Pacific oceans where they maintain cleaning stations.

Larger fish pause at these stations and perform specific behaviours which attract the cleaner fish to remove parasites from their skins.

The research team, comprised of experts from UQ, the University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland and The Zoological Society of London found that the punishment meted out by male cleaner fish toward female cleaner fish promoted cooperation and as a result rewarded the male with more food because it assured the client did not leave the cleaning station.

The Swiss Science Foundation-funded study was conducted at Lizard Island Research Station located on the Great Barrier Reef, 270km north of Cairns, Queensland.

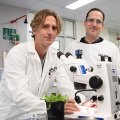

Dr Lexa Grutter from the School of Biological Sciences at UQ said: "Cleaner fish in male-female pairs cooperate to clean client fish by removing the parasites on the skins of the larger fish.

"The preferred food for the cleaner fish is not the parasites but the mucus found on the skins of the client.

"However, the cleaner pair risks having the client fish terminate the relationship if they cheat and just eat the mucus."

Cleaner fish receive all their nutrition through these cleaning services and rarely survive long in home aquariums because they cannot obtain enough food.

"Male cleaner fish punish biting females by chasing them, even though the client fish is the victim. The female then behaves more cooperatively in subsequent interactions," Dr Grutter said.

“In our study, we offered pairs of cleaner fish preferred and non-preferred food on plates which could be removed immediately if a cleaner fish ate preferred food. When the preferred food plate was removed, the male cleaner fish would chase the female," said Dr Nichola Raihani from the Zoological Society of London and lead author.

After a number of punishments, the female became more cooperative and would then continue to eat from the non-preferred plate allowing the male to obtain more food.

"The male benefits because working with a well-behaved female affords him a longer time to forage on joint clients," Dr Raihani said.

"From here, we want to further our understanding of cleaner fish breeding pairs as similar-sized female partners pose a threat to males as they can change sex and become male. We need to look at the size asymmetry in group living animals," Dr Raihani said.

Media: Dr Lexa Grutter, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia (email: a.grutter@uq.edu.au); or Tracey Franchi, School of Biological Sciences Communications Manager (telephone: +61 7 3365 4831).

.jpg)